What is stomatitis?

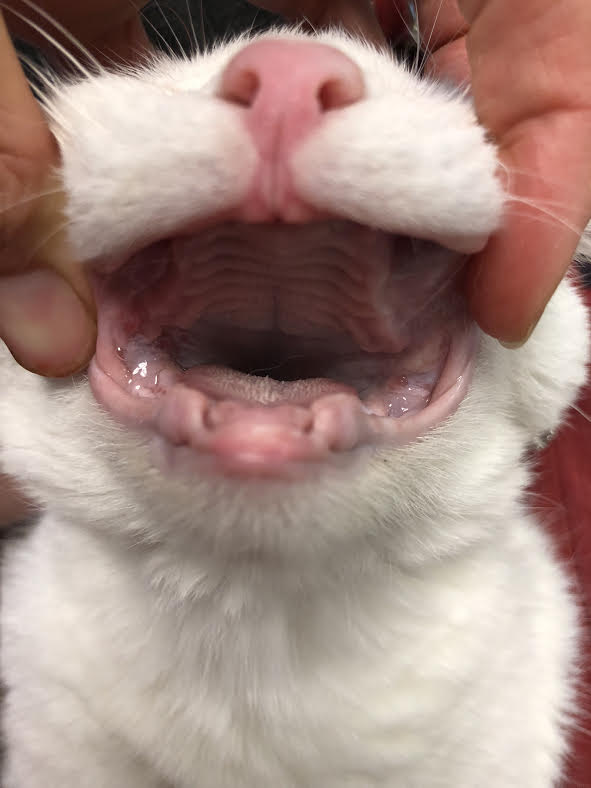

Feline stomatitis is a painful disease that we encounter all too often as veterinary dentists. It is characterized by severe inflammation of the gingiva and mucosa in the mouths of our feline patients. The classical appearance of stomatitis involves inflammation in the caudal oral cavity (far back regions of the mouth) where the upper (maxillary) dental arch extends downward to meet the lower (mandibular) dental arch. This is also known as caudal mucositis. Stomatitis is one of the few dental diseases in cats that often causes signs of pain. Clinical signs can include weight loss, drooling, dropping food, inappetence or anorexia, hiding, vocalizing/hissing at the food, failure to groom, reluctance to yawn, and halitosis (bad breath). Ideally, the oral inflammation would be noted on general examination before signs of oral pain are noticed. This gives us the best chance at a positive outcome with treatment.

What causes stomatitis?

Unfortunately, a definitive cause of stomatitis has not been identified yet. It is considered to be an atypical immune response to one or more etiologic agents. Of these, feline calicivirus and/or herpesvirus are potentially involved as research has shown that the majority of cats with stomatitis are shedding one or both of these viruses. Once in the body, these viruses become permanent inhabitants. In the majority of cats they do not cause problems, but for some, they can provoke an abnormal immune response which can manifest as inflammation in the mouth. It is possible that although these viruses do not directly cause stomatitis, they instead cause changes to the immune tolerance and response to the normal flora in the mouth (i.e. plaque bacteria). For that reason, the presence of plaque bacteria can create similar immune reactions and additionally exacerbate oral cavity inflammation. Feline bartonella has been incriminated as being involved in oral inflammation, but several studies have now shown that bartonella, if present, is not the reason for the oral inflammation. Although we advocate for Felv and FIV testing for all our feline patients, it has been shown that neither disease is related to stomatitis. However, the presence of Felv and FIV can affect clinical decision-making and treatment.

How do you diagnose stomatitis?

Diagnosis of stomatitis is generally based on the clinical appearance of the lesions. Generalized mucosal inflammation extending into the caudal (back) parts of the mouth are characteristic of this disease. It is important to note that gingival inflammation alone, even if severe, does not constitute a diagnosis of stomatitis. The inflammation must extend beyond the gingiva into the general oral mucosa and into the caudal regions of the oral cavity. Biopsy might be recommended if lesions aren’t consistent with stomatitis, such as unilateral (one-sided) inflammation.

Is there a way to prevent stomatitis?

Unfortunately, due to the fact that the cause is still unknown, there is no prevention for stomatitis. The best thing to do is to act quickly once it is diagnosed for the best chance at a successful outcome.

What is the treatment for stomatitis?

Stomatitis is a chronic inflammatory disease which often requires life-long treatment. A small subset of cases can be life-threatening when the inflammation cannot be controlled.

The first step in the treatment of stomatitis is removal of some or all of the teeth (please visit the section on coping with tooth loss). The reasoning behind such an aggressive first line of treatment involves the removal of all plaque retentive surfaces (i.e. teeth) in the mouth and thus reduction of oral bacteria. Multiple studies have shown that the majority of cats (60-80% or greater) will have a positive response to extractions. Generally, all the cheek teeth will be removed while the canines and incisors are removed if there is inflammation around them and/or signs of dental disease involving these teeth (periodontal disease or resorption). This decision is made by the treating clinician at the time of surgery. A number of cats will require oral medications following surgery to further control the inflammation following extractions. It is important to note that the prognosis is best when surgery is not delayed by multiple attempts at controlling inflammation with antibiotics and/or steroids. These treatments will have limited affect until the bacterial loads are reduced with extractions. Extractions should be the FIRST step in the treatment of stomatitis, not the final step. Another key point is that the teeth must be extracted in entirety and this should be confirmed with dental x-rays, so using a confident and well-versed dental practitioner or a board-certified veterinary dentist is vital for proper first-line treatment. Full-mouth extractions can be a very costly procedure, but performing extractions correctly the first time will prevent continued suffering and save money by avoiding the need for follow-up surgeries.

If inflammation persists to any major degree following extractions, medical management will be necessary. Regular rechecks with the surgeon are important to ensure proper control of residual disease. Success of treatment following extractions is measured by monitoring several criteria. These include reduced visual inflammation, decrease in clinical signs (as noted above), and general well-being. For those cats that have residual disease, there are multiple different treatment options out there, all of which aim to modulate and/or decrease the immune response. Use of these therapies will vary based on the treating clinician.

- Oral treatment such as antiseptics or fatty acid supplements:

- These can benefit some cats, but for those with oral pain, topically applying products can be difficult. For this reason, these products are often not applicable for stomatitis patients.

- Systemic steroids:

- Steroids are one of the more useful and commonly used treatment options due to their ability to immediately reduce inflammation and low cost. Dosage will vary based on the level of disease and the patient’s general health. Steroids can have negative side-effects, but these side-effects can be minimized over time by reducing the amount to the lowest effective dose.

- Cyclosporine/Atopica:

- This is an immunosuppressive drug (commonly used in human patients with organ transplants). It has shown good efficacy in the control of stomatitis but does not have the immediate inflammatory reduction that we see with steroids. This drug can be expensive and requires more intensive monitoring then the other drugs listed here, but most cats tolerate this medication well and it can be used long-term.

- Feline Interferon Omega:

- This is an immune stimulator meant to help the body combat an underlying viral infection. It does not have any anti-inflammatory or pain-relieving effects, but it is a safe drug with minimal side-effects. This drug is not currently approved for use in the US and can therefore be difficult to source.

- Stem cell therapy:

- Use of stem cells is still undergoing research but has shown some positive results in introductory trials. Unfortunately, it is not a treatment that is widely used or available at this time.

- Antibiotics:

- These do not have a place in stomatitis treatment and this author prefers to avoid the use of antibiotics unless absolutely necessary. Although they temporarily decrease malodor and inflammation, this is a short-lived response and can provide a false sense of security. Stomatitis is not a bacterial infection that can be controlled or cured with antibiotics, and our social responsibility to decrease antibiotic use should take precedence over our want to use them.

Case Example